Berita Terkait

- (TigaPilarNews) DPR Harap Pemerintah Ajukan Banyak Obyek Baru untuk Cukai

- [Kalteng Pos]: Akhirnya, Pemerintah Resmi Naikan Harga Rokok

- (Tempo.co) Presiden Minta Impor Tembakau Dikurangi

- RUU Kebudayaan - Rapat Baleg dengan Pimpinan Komisi 10

- (Liputan6.com) Tolak RUU Pertembakauan, Industri Kritik Sikap Kemenkes

- (DetikNews) Tugas BIN di Sektor Bea Cukai: Berantas Bisnis Rokok dan Minuman Ilegal

- Pro Kontra Kenaikan Cukai Rokok – Rapat Dengar Pendapat Umum Banggar dengan PKEKK UI

- (Kompas.com) Taufiq Ismail: Kretek Warisan Budaya Itu Akal-akalan Korporasi Rokok

- (Tribun News) Bentoel Tolak Kenaikan Cukai Rokok

- (Warta Ekonomi Online) BALEG DPR Tindaklanjuti RUU Pertembakauan

- (Tribun News) DPR: Presiden Jokowi Tak Perlu Ratifikasi FCTC

- (Guardian) Tobacco firms tried to undermine Muslim countries' (Indonesia, Egypt) smoking ban

- (Suara Karya) Jimly Asshiddiqie: UU Tembakau, UU Perbankan Harus Batal Karena Berpihak Pada Asing

- (Indopos) Badan Urusan Rumah Tangga DPR Usahakan Kompleks Parlemen Bebas Asap Rokok

- (Kompas) Larangan Iklan Rokok Dikaji: Perlu Diatur RUU Pertembakauan atau RUU Penyiaran

- (Tempo) Opini: Sikap Mendua Pemerintah Terhadap Rokok.

- RUU Tembakau - Rapat Dengar Pendapat Komisi 9 dan KomnasPT, YLKI dan ISMKMI

Kategori Berita

- News

- RUU Pilkada 2014

- MPR

- FollowDPR

- AirAsia QZ8501

- BBM & ESDM

- Polri-KPK

- APBN

- Freeport

- Prolegnas

- Konflik Golkar Kubu Ical-Agung Laksono

- ISIS

- Rangkuman

- TVRI-RRI

- RUU Tembakau

- PSSI

- Luar Negeri

- Olah Raga

- Keuangan & Perbankan

- Sosial

- Teknologi

- Desa

- Otonomi Daerah

- Paripurna

- Kode Etik & Kehormatan

- Budaya Film Seni

- BUMN

- Pendidikan

- Hukum

- Kesehatan

- RUU Larangan Minuman Beralkohol

- Pilkada Serentak

- Lingkungan Hidup

- Pangan

- Infrastruktur

- Kehutanan

- Pemerintah

- Ekonomi

- Pertanian & Perkebunan

- Transportasi & Perhubungan

- Pariwisata

- Agraria & Tata Ruang

- Reformasi Birokrasi

- RUU Prolegnas Prioritas 2015

- Tenaga Kerja

- Perikanan & Kelautan

- Investasi

- Pertahanan & Ketahanan

- Intelijen

- Komunikasi & Informatika

- Kepemiluan

- Kepolisian & Keamanan

- Kejaksaan & Pengadilan

- Pekerjaan Umum

- Perumahan Rakyat

- Meteorologi

- Perdagangan

- Perindustrian & Standarisasi Nasional

- Koperasi & UKM

- Agama

- Pemberdayaan Perempuan & Perlindungan Anak

- Kependudukan & Demografi

- Ekonomi Kreatif

- Perpustakaan

- Kinerja DPR

- Infografis

(Guardian) Tobacco firms tried to undermine Muslim countries' (Indonesia, Egypt) smoking ban

The tobacco industry attempted to reinterpret Islamic teaching and recruit Islamic scholars in a bid to undermine the prohibition on smoking in many Muslim countries, an investigation has shown.

Evidence from archived industry documents from the 1970s to the late 1990s shows that tobacco companies were seriously concerned about Islamic teaching. In 1996, an internal document from British American Tobacco warned that, because of the spread of “extremist views” from fundamentalists in countries such as Afghanistan, the industry would have to “prepare to fight a hurricane”.

BAT and other companies, which were losing sales in affluent countries where anti-smoking measures had been introduced, devised strategies to counter this perceived threat to sales in places such as Egypt, Indonesia and Bangladesh, which have large populations of young people who smoke.

The industry was concerned that the World Health Organisation was encouraging the anti-smoking stance of Islamic leaders. A 1985 report from tobacco firm Philip Morris squarely blamed the WHO. “This ideological development has become a threat to our business because of the interference of the WHO … The WHO has not only joined forces with Moslem fundamentalists who view smoking as evil, but has gone yet further by encouraging religious leaders previously not active anti-smokers to take up the cause,” it said.

“A Moslem who attacks smoking generally speaking would be a threat to existing government as a ‘fundamentalist’ who wishes to return to sharia law,” says one of the archive documents. It adds: “Our invisible defence must be the individualism which Islam allows its believers … smoking and other signs of modern living should encourage governments to a point at which it is possible quietly to suggest their benefits.”

It adds: “With Islam we might ask what other aspects of modern living are similarly open to extremist demands for prohibition under strict interpretation of sharia: motion pictures, television, and art depicting the human being? Use of electronic amplification by muezzin calling from a minaret? The education of women?” the document says.

The earliest fatwa against tobacco was in 1602, but many scholars believed smoking cigarettes or taking tobacco in water pipes or other forms was harmless until evidence of the dangers to health began to emerge in the mid 20th century. Jurists pronounced that tobacco use was makrooh (discouraged). In many Islamic countries, a harder line was taken, with smoking prohibited on the grounds that the Qur’an does not permit self-harm or intoxication.

The WHO negotiated the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, starting in 1999, in response to what it describes as the “explosive increase in tobacco use”. The convention, which outlines strategies intended to reduce demand, was adopted in 2003.

A report in 2000 from the Consumer and Regulatory Affairs (Cora) department at BAT after the first international negotiations said: “It appears that the WHO’s efforts to link religion (specifically Islam) with issues surrounding the use of tobacco are bearing fruit … We will need to discuss separately how we might understand and manage this aspect in line with the Cora strategy.”

The tobacco industry attempted to re-interpret anti-smoking Islamic teachings. A 1996 BAT memo suggests identifying “a scholar/scholars, preferably at the Al Azhar University in Cairo, who we could then brief and enlist as our authoritative advisers/allies and occasionally spokespersons on the issue.

“We agreed that such scholars/authority would need to be paired up with an influential Moslem writer/journalist … such advice would present the most effective and influential opinion able to counter extremist views, which are generally peddled by Islamic fundamentalist preachers largely misinterpreting the Koran … This is an issue to be handled extremely gingerly and sensitively … We have to avoid all possibilities of a backlash.”

Tobacco industry lawyers were also involved in this attempt at revision. A presentation from 2000, prepared by the firm Shook, Hardy and Bacon, gave an overview of the background to Islam and smoking, with slides stating that there is no prohibition on smoking in the Qur’an – and that “making rules beyond what Allah has allowed is a sin in itself”.

Prof Mark Petticrew from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who led the research, said he was amazed by what researchers had found in the archives. “‘You couldn’t make it up’ comes to mind,” he said. “The thing that jumps out at me from all this is the fact that we had tobacco industry lawyers actually developing theological arguments. That was pretty surprising.”

A document suggest Philip Morris wanted to try to recruit Islamic scholars at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. A representative of the Canadian Tobacco Manufacturers’ Council “agreed to make exploratory contact”, it says. Petticrew and his team do not know whether they were successful. “We couldn’t find the papers,” he said.

The tobacco industry is still heavily promoting smoking in countries such as Indonesia, Bangladesh and Egypt, 3 from 5 the biggest predominantly Muslim countries and have high proportions of smokers. In Indonesia, “anti-smoking” coalition condemned Philip Morris and 3 big cigarette-makers try to intervention bill about tobacco on House of representative.

Indonesia case

According to the World Health Organization, three of every four Indonesian children between the ages of 13 and 15 are exposed to cigarette ads on billboards and pro-tobacco messages at sporting events.

“In Indonesia, advertising, promotion and sponsorship went crazy after we passed the 2009 Health Law labeling tobacco an addictive substance,” says Kartono Muhammad, the head of the Tobacco Control Support Center at the Indonesian Health Experts Association (IAKMI).

“The tobacco industry has since been fighting fiercely to annul the regulation.”

The other cases have been brought by the Ukraine, Honduras, the Dominican Republic and Cuba. The latter trio, all cigar-producers, have cited concerns that the legislation covers all tobacco products, not just cigarettes.

The plaintiff countries maintain that Australia’s law breaches international trade rules and intellectual property rights to brands — arguments rejected by Canberra and which also failed to convince Australia’s High Court in a case brought by tobacco firms.

Kartono said the government’s challenge through the WTO was a questionable move, both from a health and financial perspective.

“It’s funny, why bother challenging Australia’s decision to protect its people when the policy itself does not affect us directly,’ he said.

Kartono said Indonesia did not export a massive quantity of cigarettes to Australia.

“Since 2011, Indonesian cigarettes are practically no longer sold in Australia, so economically Australia’s policy on the plain packaging will not affect us,” he said.

He said the decision to join the challenge against plain packaging policy has proved that the Indonesian government is controlled by the tobacco industry.

“Indonesia, along with some other countries, has been manipulated by the giant tobacco industry to fight their battle,” he said.

Kartono said Indonesia’s complaint to Australia was very likely driven by the industry’s demand to protect its business internationally.

Tubagus Haryo, chief campaigner for the National Commission on Tobacco Control (Komnas PT) said while the government’s effort to protect the industry was understandable, it should prioritize the health of its citizens over the concerns of the industry.

“Australia’s policy to protect its citizens with the plain packaging is commendable and should have been followed by other countries, so why would we challenge it?” he asked.

Tubagus said Indonesia has gained a lot of negative attention for being the only country who did not ratify the FCTC and for hosting the controversial World Tobacco Asia Forum for three consecutive years.

“You can imagine how we are going to look with this move, our reputation has been tarnished and it will get even worse,” he said.

According to the World Health Organization, three of every four Indonesian children between the ages of 13 and 15 are exposed to cigarette ads on billboards and pro-tobacco messages at sporting events.

The Global Adults Tobacco Survey 2011, released in 2012, ranks Indonesia second after China for the number of smokers.

The survey found that 67.4 percent of men and 4.5 percent of women in Indonesia were active smokers.

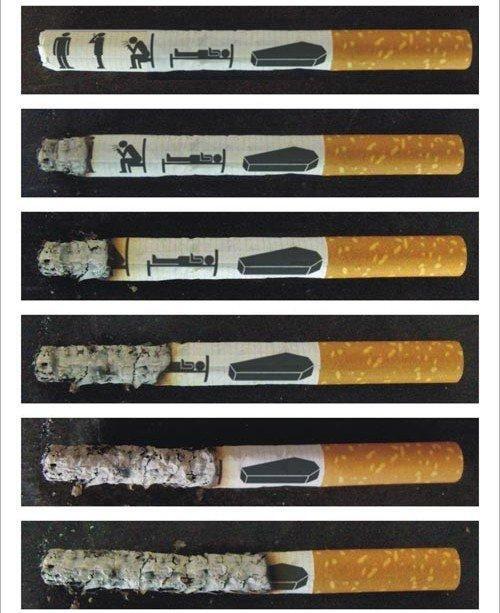

The government issued a regulation that will oblige all cigarette makers to include pictorial health warnings on the cigarette packaging in December last year. The regulation will come into effect in June 2014.

Tara said despite the government’s decision to challenge Australia’s policy on the plain packaging, the Ministry of Health seemed to be consistently committed to implementing the pictorial health warnings.

“I hope nothing will change because I can see that the health ministry is still serious about protecting public health,” he said.

Australia is forcing tobacco companies to adopt plain packaging in a world-first move aimed at reducing smoking-related deaths in the country. The Indonesian government is seeking to challenge the move through the World Trade Organization.

According to data from research company Nielsen, Indonesian tobacco companies spent Rp 1.98 trillion ($202 million) in 2010 on cigarette advertisements.

“Our children first learn about cigarettes from ads, because even though wehave agreed that tobacco is an addictive substance, we have neglected to completely ban tobacco advertising,” Kartono says.

“It’s a double standard that we have banned alcohol advertising because alcohol is considered an addictive substance, but we allow advertising for cigarettes, which are also addictive. What makes cigarettes so special?”

“We are fighting for a total ban on cigarette ads, and to be honest it’s a very hard fight,” says Ezki Suyanto, the deputy chairwoman of the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI).

Under the 2002 Broadcasting Law, cigarette ads on television may only be aired after 9:30 p.m. However, Ezki says that cigarette companies use many other methods to promote their products before then.

“In the afternoon, while children are still watching TV, you can see cigarette logos diplayed at music and sporting events, which is a form of advertising,” she says.

She added that the KPI recently reprimanded a TV station that had aired a quiz sponsored by a cigarette company during the daytime. “They argued they didn’t air any ads, but merely displayed the logo in the background. I said that even if it had just been the company colors without the logo, the KPI still classified it as an ad.”

Ezki notes that Indonesia is the only country in the Southeast Asian region that still allows cigarette ads to be aired on TV.

“In our country, after 9 p.m. the TV stations still bombard their viewers with cigarette ads, with practically no other ads being aired,” she says.

She adds the KPI has been lobbying for new regulations to challenge the current broadcasting regulations.

“What we want is a total ban, but the resistence is tremendous,” she says, adding that the KPI has been heavily criticized by television stations and legislators.

“It’s very hard to convince legislators, but we stand firm. Television and radio stations have direct access to the public, and so they have a responsibility not to promote dangerous substances,” Ezki says.

Ninety-three percent of Indonesian children are exposed to cigarette ads on television, while 50 percent regularly see cigarette ads on outdoor billboards and banners, according to a survey conducted by the National Commission on Children Protection (Komnas Anak), cooperation with Tobacco Free Kids.

Tjandra Yoga Aditama, the Indonesian Health Ministry’s director general for disease control and environmental health, says the ads are designed to give impresionable youths the impression that smokers is “cool and confident.”

“While we believe that most children start smoking because of peer pressure, the process actually starts long before that, because our children are constantly exposed to cigarette ads. It’s just a matter of time before they take up smoking,” he says.

The WHO says that although most countries have tobacco control laws, a ban on advertising of tobacco products needs to be enforced.

“Statistics show that banning tobacco advertising and sponsorship is one of the most cost-effective ways to reduce tobacco demand,” says Samlee Plianbangchang, the WHO’s regional director.

“A comprehensive ban on all tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship could cut consumption by an average of about 7 percent, with some countries experiencing a decline in consumption of up to 16 percent.”

The Global Adults Tobacco Survey 2011, released in 2012, ranks Indonesia second after China for the number of smokers.

The survey found that 67.4 percent of men and 4.5 percent of women in Indonesia were active smokers.

Indonesia passed a long-awaited tobacco control regulation that imposes certain restrictions on cigarette advertising.

One of the restrictions will bar companies from portraying children, teenagers or pregnant women in their ads. The ads are also prohibited from glamorizing smoking or encourage people to take up the habit.

The regulation will require cigarette ads on television to devote 10 percent of their running time to written warnings with a pictorial warning. Ads on the radio would have to devote 10 percent of their duration to verbal warnings, while still-image ads would be required to devote 10 percent of their area for a warning.

The regulation also stipulates specific prohibitions for cigarette ads in print media. One of them is that these ads may never be published on the front or back cover of a print publication or near ads for food and drink products. Cigarette companies are also barred from taking out a full-page ad in any print publication.

Restrictions on outdoor media advertising include a prohibition on tobacco ads being displayed in smoke-free zones or along main roads.

The restrictions, however, will not apply to small-scale tobacco companies, defined as those that produce fewer than 24 million cigarettes a year.

“A partial ban is even more dangerous than no limitation at all,” says Lisda Sundari from Lentera Anak Indonesia, a non-government organization focusing on advocating children.

“It’s a manifestation of half-hearted protection for our children.”

Its marketing is generally adapted to the “not overly devout”, says the study. The authors call for further research to find out how the industry had approached other faiths.

Global problem

“The launch of the Faith Against Tobacco national campaign by Tobacco Free Kids and faith leaders in the US, for example, brings together Christianity, Islam, Judaism and other faiths ‘to support proven solutions to reduce smoking’. Understanding efforts by the industry to undermine the efforts of other faith communities brings to light a broader strategy to marginalise tobacco control in diverse communities, and refocuses the problem on tobacco-related health harms,” says the paper.

BAT told the Guardian. “This study, which concerns material written nearly 20 years ago, does not represent the views, policies and position of British American Tobacco. We are a global business that holds itself to strict standards of business conduct and corporate governance, manufacturing and marketing our products in accordance with domestic and international laws and observing the cultural and religious beliefs in the 200 countries in which we operate.”

Philip Morris did not respond to the Guardian’s request for comment.

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/apr/20/tobacco-firms-tried-undermine-muslim-countries-smoking-ban